Fighting Cancer

Martha Grossel takes on the leading cause of death worldwide as a professor and researcher.

Cancer just keeps killing. As the second-leading cause of death in the United States, it takes nearly 600,000 lives every year.

Thankfully, though, cancer researchers continue to make breakthroughs and cancer death rates among men, women and children are finally declining. The most recent Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, published in March 2016, shows that from 2003 to 2012, cancer death rates decreased by 1.8 percent per year among men, 1.4 percent per year among women and 2 percent per year among children ages 0-19.

These percentages might not seem large, but to those with cancer the decreases mean life.

It isn’t hyperbole to say these percentages are decreasing thanks to the work of scientists such as Connecticut College biology professor Martha Grossel.

Grossel is a cancer researcher anda teacher. She’s engaged in the battle to fight cancer, and she’s training future researchers to carry the fight forward.

“Science is hard; you work really hard and oftentimes you don’t have anything to show for it at the end of the day—or the week,” Grossel says.

“Sometimes the data, the results don’t tell us what we expected; it doesn’t fit together, or your ideas are wrong, and so that’s intellectually challenging. I love solving the puzzle that that is. But it also can be very difficult.”

That’s where teaching is the perfect complement.

“Training students is the opposite,” she says. “Students are so appreciative. If a result doesn’t work out the way you’d hoped it would, they learn, regardless. It’s so fun to watch. It’s definitely the right balance for me.”

Grossel’s contributions include earning $1.5 million in federal research grants, including $419,375 in 2015 from the National Institutes of Health’s National Cancer Institute, which awards money to only 14 percent of all grant applications. That grant was for further study of the cdk6 protein and how it interacts with the Eya2 protein, which is important for understanding breast and ovarian cancers.

The money is vital—“everything we buy is expensive; you buy an antibody, it’s $300”—to enable her, her colleagues and students to work with state-of-the-art equipment.

So, what does Grossel do?

Well, there’s that cdk6 protein, which is a “D-Cyclin-activated kinase that phosphorylates the retinoblastoma protein (pRB) in the G1 phase of the cell cycle.”

In layman’s terms, Grossel’s research focuses on understanding the cellular division that is associated with cancer. She says one of the factors that makes her a strong teacher is her ability to translate complicated subject matter for nonscientists.

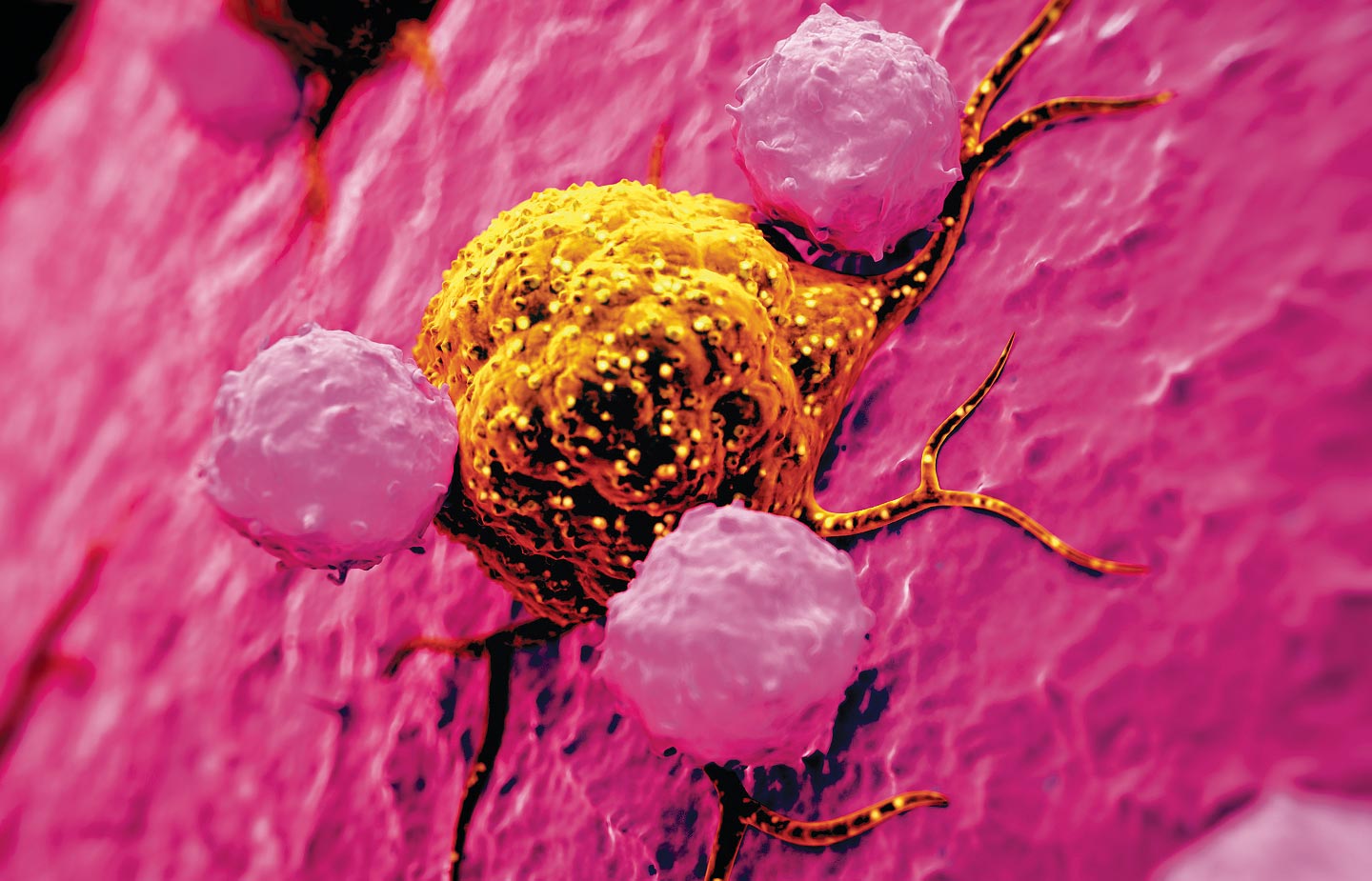

“We do really basic research studying what triggers a cell to divide. And if we can understand that, then we can try to stop it when it becomes unregulated. Basically, cancer is just a cell that stopped acting the way it should; it lost the normal controls that contain it and its division.”

Grossel recalls an “aha moment” several years ago as she and two colleagues struggled to understand the interaction of cdk6 with another protein, Eya2.

“We were all taking different approaches to trying to understand the interaction of these two proteins. It wasn’t making sense. And one day we all sat down and were talking about it and looking at all our data. And working together like that allowed us to come up with part of the missing puzzle piece that this one protein, cdk6, is causing the Eya2 protein to be reduced. And that allowed us to take the next step in the research, to understand how that then influences cell division.”

The more researchers understand cdk6, the closer they are to developing treatments for certain types of leukemia and brain tumors. Indeed, work like this has, in part, led to a newly developed drug for breast cancer by Pfizer.

“Through her work, we are gaining a better understanding of what goes awry during tumor development,” says one of Grossel’s former students, Vasilena Gocheva ’04, collaborative programs manager at the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT, which has five current and former faculty who have been awarded the Nobel Prize.

“Martha works in a very important area of cancer research and her findings have helped move the field forward. By elucidating novel functions of cyclin dependent kinases, her research could lead to new therapeutic options.

“Working with Martha was the single most important experience for me at Connecticut College,” Gocheva says.

“She is the one who inspired me to go into cancer research. She challenged me to think independently and taught me how to problem solve. Martha truly cares about her students and their future, and also gave me a lot of guidance, and that didn’t stop when I left Conn.”

Grossel says that networking with colleagues such as Gocheva and others helps keep her fresh.

“The world I live in, cancer research, moves so fast that it’s hard to stay on top of it because I teach so much.” The networking “really helps me stay in touch with what’s going on and keeps my science up to date.”