Art in Lockdown

Professor of Art Timothy McDowell and his students find ways to create while studying remotely.

There’s a popular myth that the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes would climb into an old oven to escape the distractions of daily life, only to emerge with creative new takes on the human condition and groundbreaking geometric theories. Today, Art Professor Timothy McDowell, in his 40th year at Conn, and his students are mining inspiration from pandemic-induced isolation.

CC Magazine: How has this unprecedented time of working remotely changed the way you approach your job?

Timothy McDowell: This current situation has obviously required some adjustment, because in a studio environment, normally we’d be walking around and offering constructive feedback on each other’s work and offering advice on process or nudging each other to improve a project. At the moment we’re viewing work on screens where the work isn’t quite as clear or well defined. But despite that challenge, we’ve continued to keep the dialogue going and the minds working to create things.

CC: Why is it so important to do whatever is necessary so that students can still access art and have the opportunities to create it?

TM: This is essential to the well-rounded approach of the liberal arts. We need to keep feeding both sides of the brain and keep the creative and inventive connections between the brain and the hand and the mind strong. I was just telling my class that this situation has required reinvention, and reinvention is one of the most creative and important things a person can do. We need to look at our situation and find new ways of achieving our goals.

CC: Have the stay-at-home requirements impacted you and your

art personally?

TM: For a lot of studio artists, since we spend so much time alone anyway, the solitude might not feel so foreign and difficult. There’s really no way to be in a studio and concentrate and be creative if there’s a crowd there, so personally the isolation hasn’t been so bad. I’m very lucky to have my studio attached to my house. I’ve felt fortunate to be able to find more moments here and there where I can duck into my studio and do some work or truly concentrate on what my students are doing. Finding those spontaneous moments can be difficult when I’m at work surrounded by people.

CC: How has the pandemic changed your process or affected your job as

an artist?

TM: For one thing, the pandemic has obliterated the gallery world. At the moment, it’s not possible to attend openings and exchange ideas with people while looking at work firsthand. You can view art online, but it isn’t the same. There’s no tactile reference.

I had a solo exhibition planned for the beginning of June that’s now on hold, and I don’t know when it will occur. I was working toward that exhibition concerned about issues like economic inequality, greed, and political and financial polarization. The work was inspired in part by another time in history when a pandemic took hold, during World War I, and those events influenced art. I hope that when this exhibition is finally seen, I’ve created a body of work that causes viewers to stop and engage each piece as a part of a larger puzzle. But I’m exploring new places as an artist that I’ve never been. What better time to reinvent yourself than at a time when the whole world is having to reconstruct how it functions?

CC: Since you’ve had a show postponed indefinitely, you can identify with students who won’t have their final exhibitionsor attend the many end-of-year ceremonies that seniors, in particular, look forward to. What advice have you given your students about coping with this disappointment?

TM: I think it’s important to remind them—and I know they understand

this—that they’re making art for themselves and feeding their own need to create art. The exhibition at the end should be seen as the icing on the cake of that creative process. It isn’t the exhibition that makes the artist—it’s the artwork that makes the artist. I know that the activity of being in the studio or at home and making something and imagining an exhibition can be motivational sometimes, because there’s an impetus to participate and display and share your work. But you’re making art because you have a need to do it. It makes you feel whole. It allows you to have a dialogue about the events in your life.

CC: Are you considering other ways for your students to share their work with the Conn community?

TM: We’re thinking about putting together a catalogue of their work that can be printed and shared, and we’ll probably create a website with all the projects. We would also definitely still like to have an opening once we’re back on campus, and those students who have recently graduated who are able to come back would certainly be invited to participate.

CC: Have there been any pleasant surprises or positive aspects of remote teaching that you didn’t expect to encounter?

TM: I’ve been impressed with how well students have adjusted and adapted. I think part of this is thanks to a generational exposure to technology. They’ve grown up used to creating and interacting with screens, and so I think that has helped. I also think they’ve had greater access to me or have taken advantage of video conferencing to discuss their work and have learned to plan and manage their time in new ways. I’m having more brief video chats with students where we just check in, which I really like. It’s much better and more personal than just reading an email, so I hope that new piece of our daily communication remains after we return to normal.

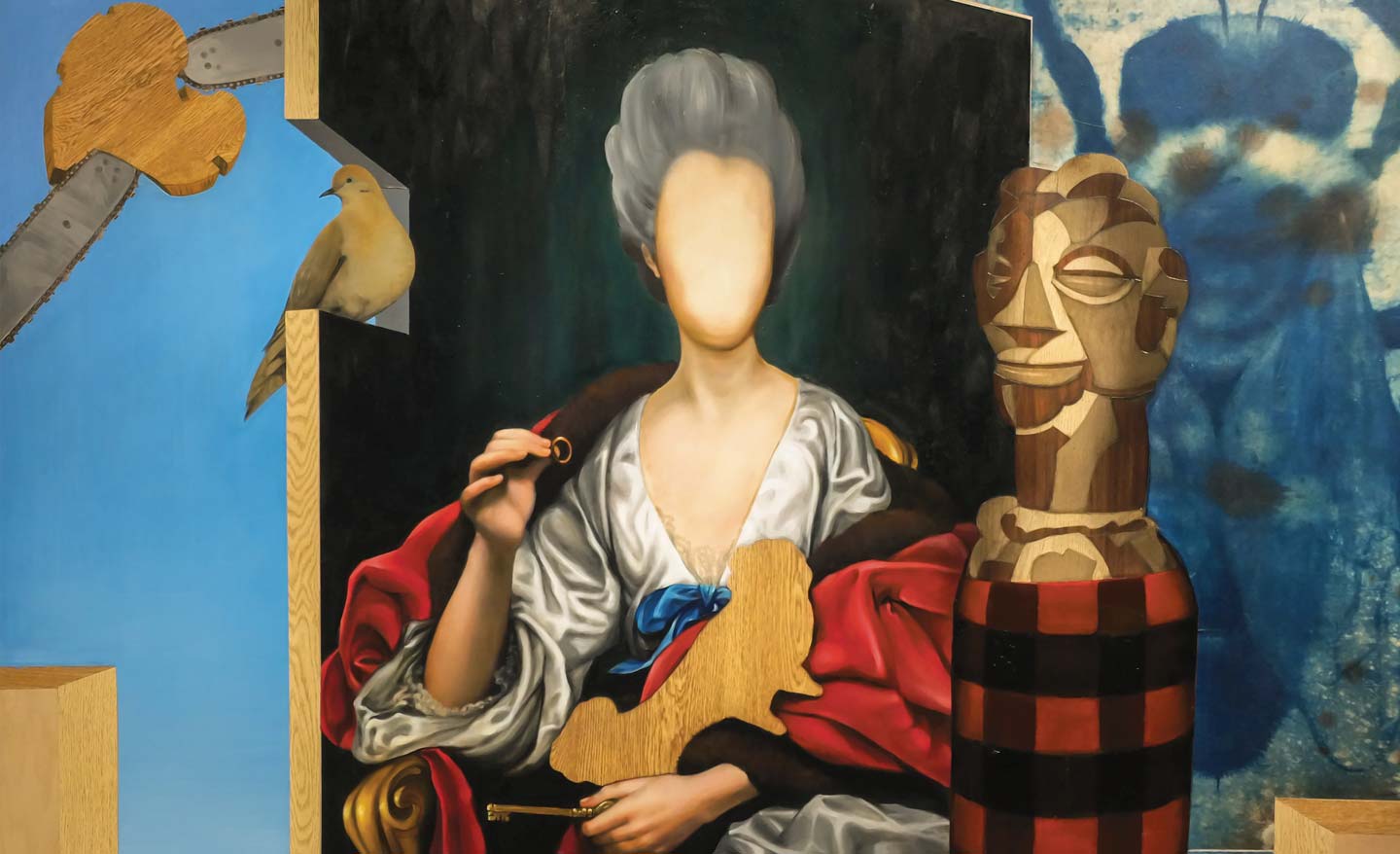

Artwork at top: Timothy McDowell, Blind Love (detail), 2020, Oil on Panel, 48” x 48”