Existence Is An Oddball Thing

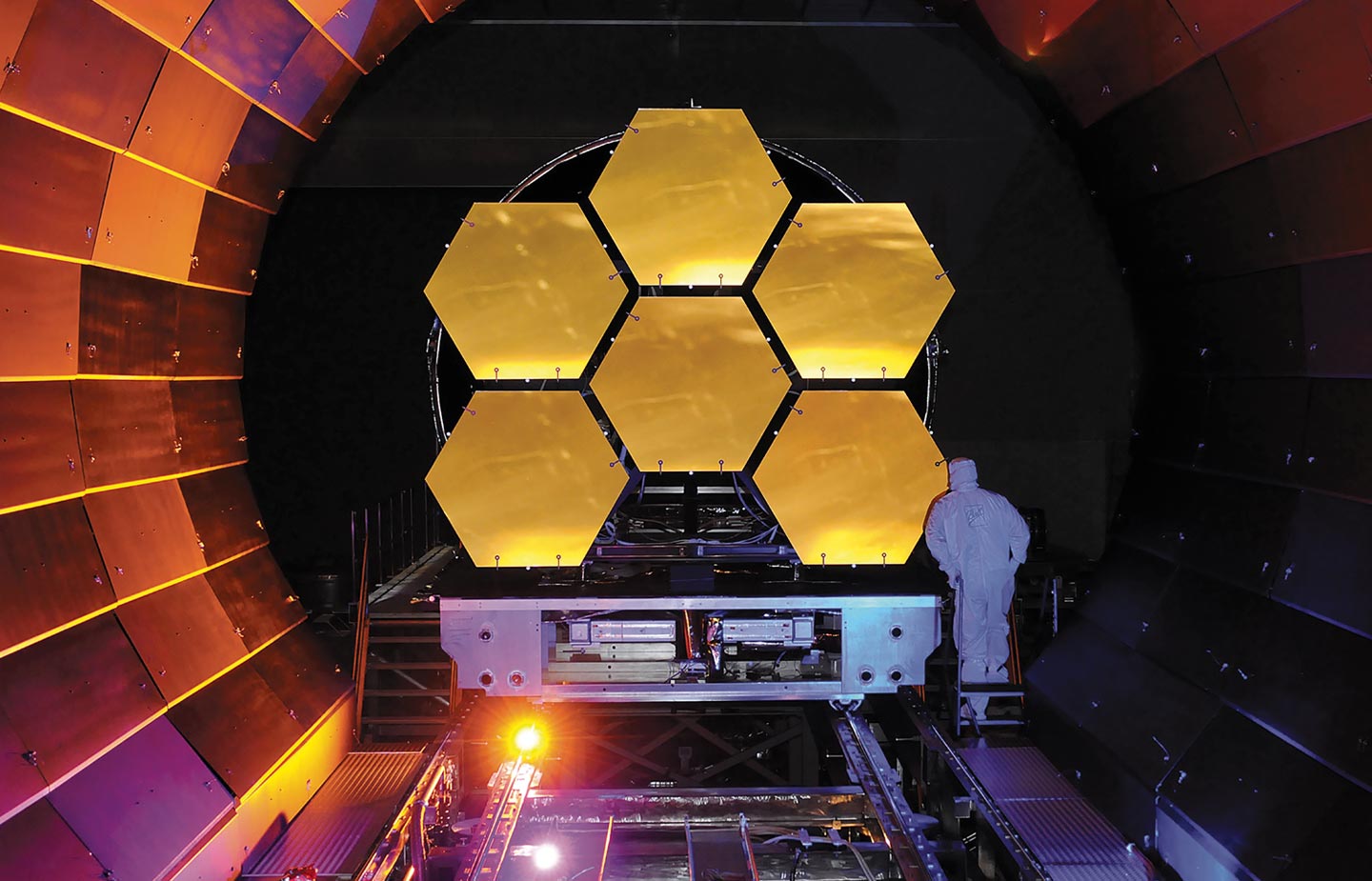

Astrophysicist Samuel Harvey Moseley Jr. ’72 worked on a key component of the James Webb Space Telescope, the most powerful telescope ever launched into space.

Samuel Harvey Moseley Jr. ’72 wasn’t too nervous when NASA launched the James Webb Space Telescope—the largest and most powerful ever—into space on Christmas Day, 2021.

But the astrophysicist, who conceived of and led the development of Webb’s microshutter array, a key technological component that enables the telescope to take photographs of deep space, did hold his breath a few weeks later as the otherworldly looking contraption unfolded its giant mirror wings far from Earth.

“I knew where the complexities were in the system, and I knew the steps that were most critical for the microshutters. It turns out the biggest mechanical impulse they get is not during the launch but when the side wings on the mirror are released,” said Moseley, now the vice president for hardware engineering at a New Haven-based quantum computing startup, Quantum Circuits.

Moseley watched the progress with his friend and longtime colleague John Mather, the senior project scientist for Webb. The two worked together on Webb beginning in the late 1990s and, before that, on the Cosmic Background Explorer mission (COBE), which confirmed the Big Bang theory and for which Mather won a Nobel Prize.

“We were trying to see how it was going, and he’s absolutely calm. He said, ‘We did everything we needed to do. We found everything we could find, and we tested everything. We have to be OK with that,’” Moseley recalled Mather saying.

Mather had every reason to trust Moseley’s design for the microshutters, a series of 250,000 tiny windows with shutters that open and close to allow the telescope to record and measure up to 100 distant galaxies at once, including some of the very first galaxies formed after the Big Bang.

For decades, Moseley had been the figure-it-out guy at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center—the one who could solve complex mathematical equations and invent the technologies to measure and record ever deeper into the cosmos. And in January, he was awarded the National Academy of Sciences’ 2022 James Craig Watson Medal for his contributions to the development of astronomical detectors that have “profoundly changed our understanding of the universe.”

Once again, one of Moseley’s designs is working: On March 16, NASA released stunning test images of a star (called 2MASS J17554042+6551277) with other galaxies and stars clearly visible behind it. The images, Webb deputy telescope scientist Marshall Perrin told CNN, “are focused together as finely as the laws of physics allow.”

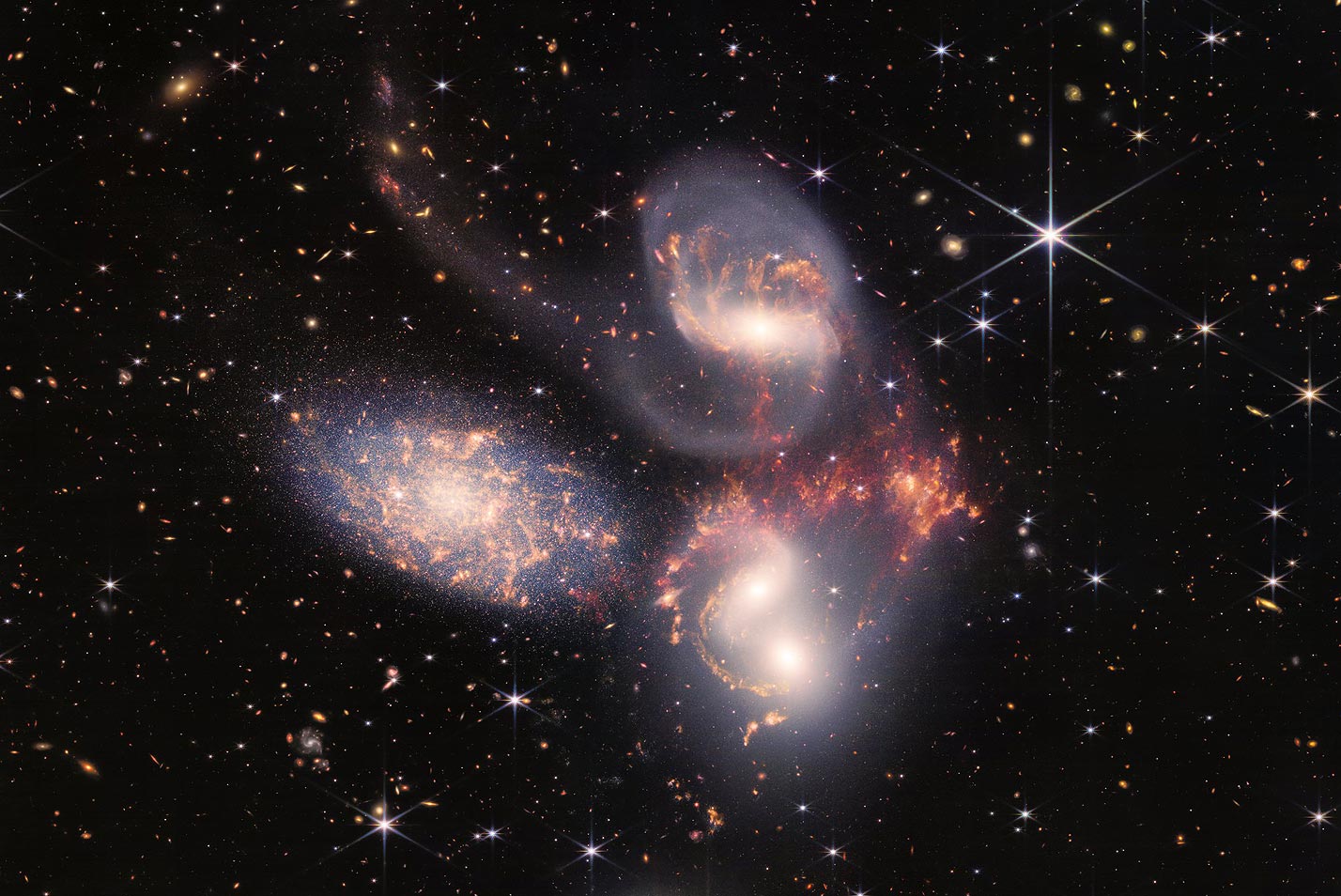

Webb wasn’t launched just to produce pretty pictures of stars. The telescope will possibly bring into focus the very first generation of objects to form after the Big Bang. It might answer all sorts of interesting questions, Moseley said, like “‘How do galaxies form and grow?’ ‘How do supermassive black holes in the cores of galaxies grow over time?’”

The working theory is that there are mergers of galaxies over time, an absorption of one galaxy by another. Understanding this process can teach us about how, 13.8 billion years after the Big Bang, our world came to be.