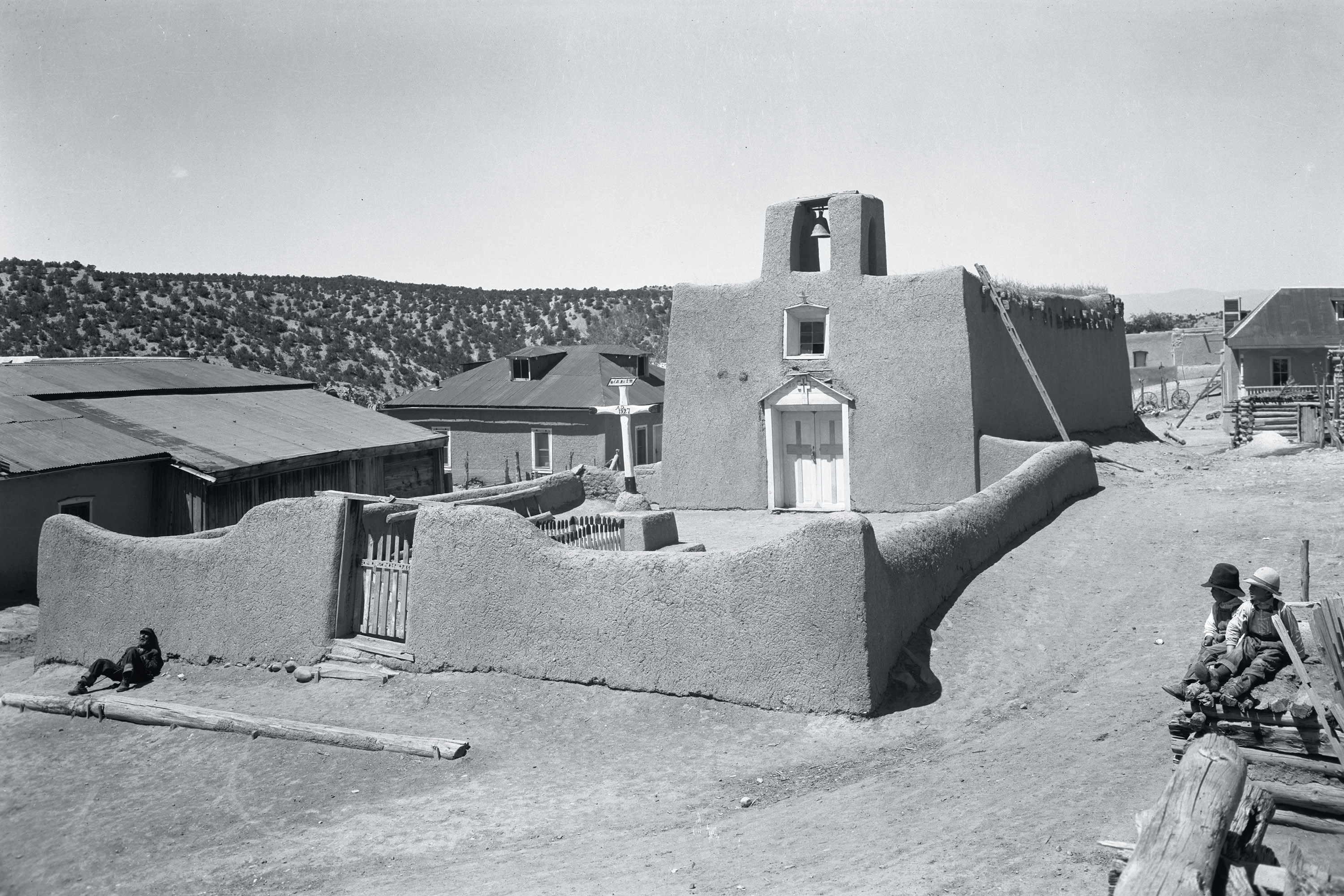

Adobe Mission

Professor Emeritus Frank Graziano is working to preserve New Mexico’s cultural heritage one historic church at a time.

After retiring from Connecticut College in 2016 I moved to New Mexico—a spectacular setting on the Río de las Trampas, surrounded by national forest. The house was less spectacular. For the first months I lived in a hellish, unfurnished construction site, with a mattress on the floor and contractors competing for achievement in decibels, but eventually the renovation was complete, a sense of home ensued and the silence conducive to reflection resumed. I could hear myself think.

Often that gets me into trouble. I had always been drawn to New Mexico’s adobe churches, probably as part of a broader fascination with folk art. The churches exude a mood and charm that elicits a response as much emotional as it is aesthetic. They are humble and human, unpretentious, massaged with mud into funky formal imprecision out of square and out of plumb, swelling and receding, with mass and bulk yielding somehow to grace and synesthetic softness. The churches seem to emerge from the earth like giant sculptures inherent to environs that background the composition. At isolated rural churches especially, the adobe, the landscape and the sky fuse into a single perceptual experience ratified by silence, while inside cool air contrasts with visual warmth and the enclosed silence somehow feels denser, almost tactile. And the churches stand before us as symbols: of faith, of history and heritage, of cultural identity and place attachment, but also of vulnerability, change and obsolescence.

Shortly after settling in New Mexico I began to research the possibility of writing a book on historic churches. I discovered quickly that there was significant (and redundant) scholarship on the churches’ history, art history and architecture, but there was nothing on what seemed most compelling: the status of the churches and their congregations presently, given the apparent disuse and need for restoration. A hybrid method at the nexus of history and ethnography had been my approach in other recent projects, so I drafted a proposal along these lines, sent it to my editor at Oxford University Press and waited the requisite seemingly forever for the response. It came finally and was positive, with a contract for writing Historic Churches of New Mexico Today, and the book was eventually published in 2019.

I spent several months interviewing parishioners, church mayordomos (caretakers), priests, pilgrims and hermanos penitentes (members of the lay brotherhood Los Hermanos de la Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno). It became clear rather quickly that rural churches—known here as missions—were in a precarious situation because their villages were largely depopulated, because society had become more secular, because the community culture of maintaining churches had weakened, and because the parishes and archdiocese were not in financial positions to maintain or restore churches that were rarely used. An avalanche of other factors likewise contributes to the churches’ demise: conversion to Protestant churches, self-identifying Catholics who do not practice the faith, fragmentation of the nuclear family, functional obsolescence of the buildings, unviability of small-scale farming and consequent migration and resettlement out-of-state for employment, shortage of priests and mayordomos, and centralization of the sacraments (small local congregations gather at the mother church rather than the priest visiting each mission individually).