Building an equitable future

A collaboration between Connecticut College and the New London community is bringing the past and present together, in hopes of a more just future for residents of color.

The Connecticut College initiative is part of “Crafting Democratic Futures: Situating Colleges and Universities in Community-based Reparations Solutions,” a three-year collaborative project supported by a $5 million grant to the University of Michigan from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The goal of the project is to bridge the gap between colleges and communities and explore reparations for African American and Indigenous communities.

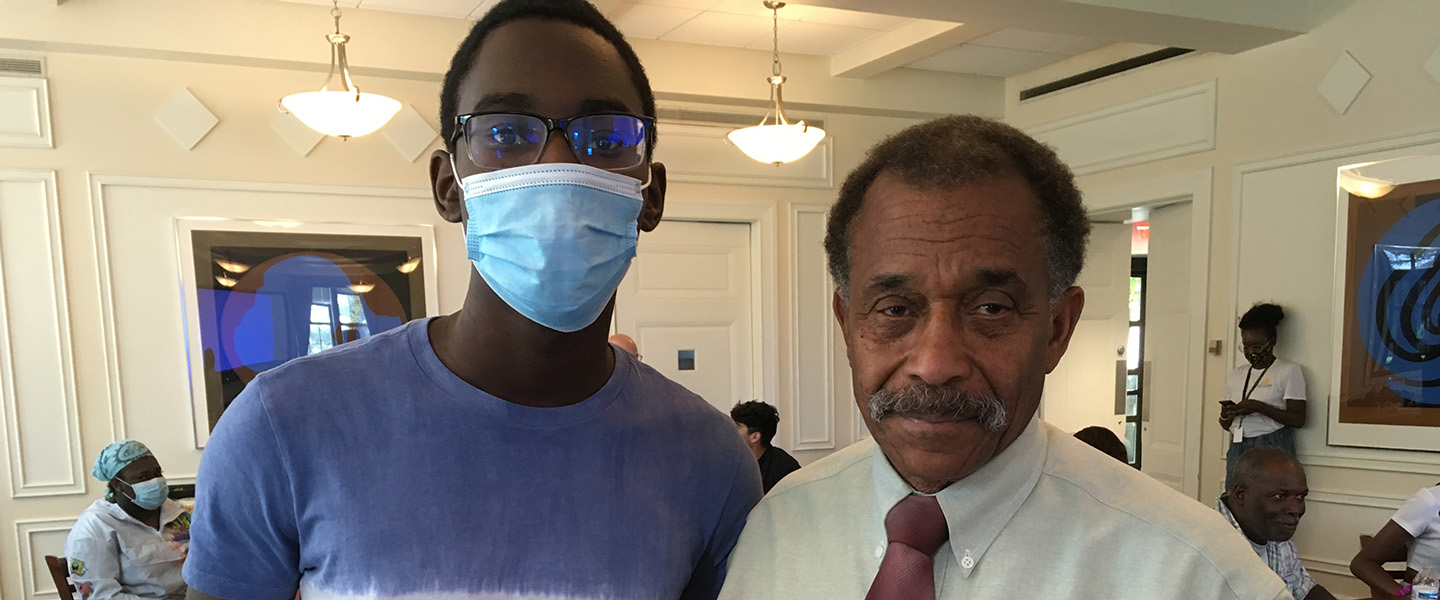

William Meredith Assistant Professor of Psychology Nakia Hamlett and Faulk Foundation Professor of Psychology Jefferson Singer, the principal investigators on the $275,000 grant to Connecticut College, have paired high school students with people of color in the community to conduct interviews about residents’ experiences of systemic racism and discrimination.

Throughout the project, narratives pulled from these interviews will be collected and analyzed by Hamlett and Singer, along with the help of undergraduate students. These analyses will be shared with their community partners with goal of disseminating the findings to the larger New London community in a variety of public venues and formats.

“From its inception, we thought of this as a community project,” explained Hamlett. “This drives our focus, because we want something that will have tangible action steps.”

The community partners working with Conn include the New London Public Schools, the Church of the City of New London, Shiloh Baptist Church and the retired executive director of the Jewish Federation of Eastern Connecticut. In early discussions between the College and these community leaders, one main issue of inequity was often discussed: historical redlining—the systematic disenfranchisement of communities of color by denying them mortgages and other financial support.

It’s thought that findings from the interviews of people who have lived through redlining in New London, might lead to reparations initiatives, whether that means working with the local council or financial services providers who have historically redlined communities.

Grounding Conn projects in the New London community has always been important, explained Singer: “That culture has been at the College for a long time, and I think it’s very powerful in engaging students in different ways with the community.”

College President Katherine Bergeron echoed Singer’s sentiments.

“We are thrilled to be part of this ambitious national undertaking,” said Bergeron. “The Mellon grant builds on Connecticut College’s longstanding history of community action and public policy. The focus on reparations and long-term change aligns with our strategic goals for full participation and with our mission of educating students to put the liberal arts into action as citizens of a global society, a mission that has never been more critical.”

Bergeron currently serves as chair of the board of directors of The Council of Independent Colleges, an association of nearly 700 institutions of higher education, which is supporting the grant’s four participating CIC member colleges.

Central to the project is the help of Conn’s Holleran Center for Community Action, which connects campus to community through social activism and civic engagement.

“As a native New Londoner, I’ve always felt it essential for the college to continuously strengthen its relationship with the local community,” said Civic Engagement and Communications Coordinator Clayton Potter, who is helping in all facets of the project, including assisting with the training of the high school students in narrative interviewing and learning about the history of New London.

“Intentionally and frequently inviting New London community members to take advantage of college resources is what makes Connecticut College part of the community and not the ‘college on the hilltop.’”