What the Eyes Don’t See

Mona Hanna-Attisha discusses her role in exposing the Flint water crisis in the One Book One Region finale event hosted by Connecticut College.

Watch the full One Book One Region finale event on YouTube.

“Is this filtered water?” Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, a pediatrician from Flint, Michigan, joked as she lifted a full glass from the table next to her seat on the Palmer Auditorium stage at Connecticut College.

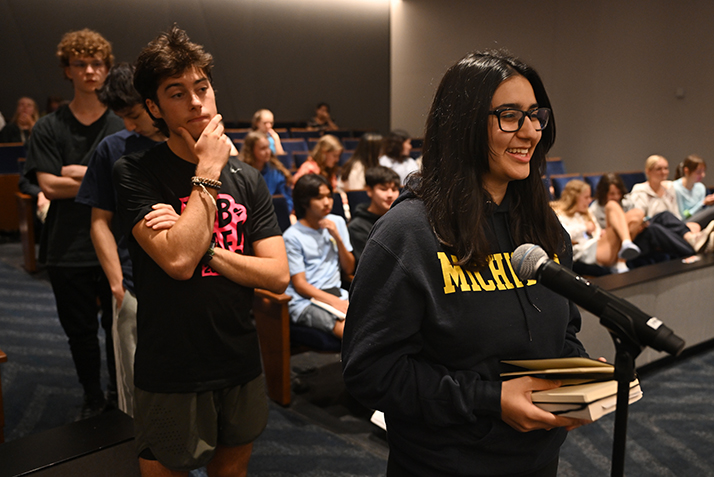

A crowd of students, faculty, staff and community members were in attendance to hear her discuss her book, What the Eyes Don’t See: A Story of Crisis, Resistance, and Hope in an American City, in conversation with Associate Professor of Sociology and Environmental Studies Julia Flagg, who has published extensive research related to climate change, disasters and environmental justice.

Along with a team of researchers, parents, friends and community leaders, Hanna-Attisha discovered in 2015 that Flint residents were being exposed to lead after the city changed its water source the previous year from Lake Huron to the Flint River. The new water source wasn’t being treated with corrosion inhibitors, so the pipes it passed through were leaching lead into the drinking water. The pediatrician was worried—lead exposure can cause long-term cognitive, behavioral and health problems, especially in children.

On Sept. 20, the College hosted the personable doctor for the finale event of the area’s One Book One Region program, a collaboration that began in 2002 among the libraries of eastern Connecticut to bring community members together to discuss ideas, broaden appreciation of reading and break down barriers between people. As part of the program partnership, the One Book One Region selection serves as Conn’s summer read each year and the College hosts the author for a public lecture each fall.

After taking the stage and joking about her glass of water, Hanna-Attisha got serious. “This is the interesting thing about water: So many people don’t know how or where we get our water,” she pointed out. “It’s such an invisible system, which is one of the reasons the book is called What the Eyes Don’t See.”

The book details Hanna-Attisha’s fight against the austerity policies and bureaucratic indifference that endangered Flint. In 2015, her best friend, Elin Ann Warn Betanzo, an engineer and certified water operator, told her about the lack of corrosion inhibitors in the new water system and the resulting possibility of lead contamination.

To explore this scary possibility, Hanna-Attisha began a new research study using electronic medical record data from more than 1,700 children in the city. She found that the percentage of children aged 5 and younger in Flint with over 5 micrograms per deciliter of lead in their blood had increased from 2.1 percent to 4 percent after the water source switch.

She shared her findings at a press conference in September 2015. The next day, Flint issued a health advisory for residents, especially children, to minimize their exposure to tap water. But Michigan’s Department of Environmental Quality accused Hanna-Attisha of being an “unfortunate researcher” who was “splicing and dicing numbers” and causing “near hysteria.”

The Detroit Free Press soon published its own findings—consistent with hers—and she met with Michigan’s chief medical officer. Finally, the State of Michigan said it agreed with Hanna-Attisha’s findings and publicly acknowledged the crisis. Department of Environmental Quality officials later apologized to her.

Hanna-Attisha’s work continues today. She advocated for Congressional funding to build an environmental exposure registry for Flint residents modeled after the World Trade Center registry. The data is alarming. About 70 percent of the students evaluated have required accommodations for issues like ADHD, dyslexia or mild intellectual impairment, while adults have higher rates of hypertension. All of those conditions are related to lead exposure, Hanna-Attisha said.

“But like most environmental issues it’s very difficult to prove causation, which is why environmental culprits have often evaded accountability. There’s a time lag between exposure to when you have symptoms. But we’re not trying to prove causation—we’re just trying to support people.”

The voluntary Flint registry currently has about 20,000 people enrolled, she said, and it helps connect victims to services. About 30,000 referrals have been made so far.

Hanna-Attisha recently testified before Congress regarding the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which includes $15 billion for the replacement of lead pipes around the country. “I shared the Flint story and why we need to stop having Flints. When I testified, I said Flint’s crisis wasn’t the first, and it wasn’t the worst, and it wasn’t the last. These environmental injustices have been happening for a very long time.”

Flagg asked what Hanna-Attisha thought made Flint more egregious than other cases of environmental inequality or environmental racism the U.S.

“I think it’s a combination of issues,” Hanna-Attisha replied. “It wasn’t just about what happened environmentally. It was also a story about democracy. Flint’s democracy was usurped. Overnight, our local government lost control and we were taken over by state-appointed emergency managers. And this wasn’t just happening in Flint, it was happening throughout Michigan in majority-minority communities. At one point, half of our African American population was under emergency managers, compared to just 2% of our white population.”

Hanna-Attisha said one of the reasons she wrote What the Eyes Don’t See was “to share the story of what happens when we corrode our democracy, which is now an ‘everywhere’ story, where so many efforts are underway to take away people’s voices, to take away their vote, to take away their seat at the table—and often that is taking away the voices of minority people.”

She also pointed out the link between Flint and the recent COVID health crisis. “It’s the same lesson of public health injustices. It’s about denial of science. It’s about disinvestment in what keeps us healthy. It’s about our lack of investment in public health infrastructure, like surveillance systems, to do what we need to do. It’s about inequality—not all people are impacted by public health issues the same.”

Part scientific thriller and part memoir, the book also includes information about Hanna-Attisha’s early life and family. She said, “Originally, it was just going to be the Flint story with me as a doctor at the center of the crisis, but within writing chapter one I realized that it was impossible to tell you the Flint story without telling you who I am and where I came from.”

Her story is “an immigrant story,” she said. “I came here for the American dream. I came here for freedom and opportunity and democracy. That immigrant perspective made me committed to service, pushed me to medicine, pushed me to work in places like Flint and Detroit. And in some way, I feel it gave me this heightened antenna for injustice.”

At the same time, Hanna-Attisha said anyone can speak up and make a difference. “I’m not any superhero or special person who did this work,” she explained. “I am just like you and if I can do this work, you can do this work.”